The conflict and the privilege of MIT

I didn't think I could come here, yet here I am, and that made me question everything

The arrival

It feels very strange to be writing this. I never thought I would be writing as a student at MIT but after a rollercoaster of events I was given the opportunity of a lifetime: the opportunity to study at MIT.

I applied to MIT as a high school student, and after being rejected, I never thought that I would be here. One year ago, MIT was not in my plans, and yet, here I am. Being here feels surreal, and it still gives me goosebumps.

Part of me just wants to write about what it feels like to be here at MIT. I wish everybody could experience this crazy, amazing place: the golden sunshine that showers the dome behind Killian Court; the peaceful calmness that comes from watching the waves move in the Charles River; the confusion of getting lost in the tunnels; and the vitality of the students that resounds in the hallways, the lounges, the streets, and even the silent libraries. I could never describe the smells, the colors, the textures, the architecture, and most importantly, the people. The people are the most profound aspect of being here, because even though I have visited this place before, I didn’t understand the MIT community until I became a student. Before I arrived at MIT, the thought of studying at MIT brought joy and fear. I questioned what it would mean to be an MIT student and why I was given this opportunity out of the hundreds of applicants. I cannot claim that I am better than any of the other applicants, and I personally don’t feel as if I am better than any of them. If that is true, do I deserve to be here? My story and the purpose that I expressed in my application brought me here, but during the application process I began to question both my career as a scientist, and my value as a human.

————————————————–

The paths I walked

I come from a tiny town in Guanacaste, a province in the northwest of Costa Rica. I’m the youngest of seven siblings, and my mom raised me the best she could as a single mom and a college dropout. Growing up poor is not just about economic scarcity, but about the conditions and circumstances that hold you back in life and become “endemic” to poor communities. Alcoholism, drug addiction, lack of opportunities, domestic violence, machismo, and well, homophobia permeated most of my upbringing, and I remember vividly focusing on surviving most of those experiences when I was young.

I gained access to educational opportunities by relying on my own skills and resourcefulness. I left my hometown at the age of fifteen to spend the last two years of high school in an elite school that placed me on the path to go to college. The journey that followed is similar to many others; like many at MIT I was a driven student who got involved in research early on in my career, volunteered actively for causes I cared about, and then managed to obtain funding to pursue internships and study abroad experiences in California, Lisbon and Virginia. I landed a fully-funded scholarship from the European Union to complete a Master’s Degree in Nanotechnology. During that program, I learned that most technological innovations happening at the forefront of science are not targeted at improving the quality of life of most people or even people at the bottom of society. On the contrary, scientists may inadvertently end up aggravating inequality and systems of oppression by making innovations accessible only to a few privileged people, and not the majority of people. When we don’t question why we are conducting research, who are the involved stakeholders, what is the role of science in society, and what are the long-term impacts of unleashing new technologies into the world with little to no regulations, we can propagate inequality. This realization made me forgo a career in nanotechnology research and start anew in pursuit of a career in policy studies. I was determined, and I saw I could do much more to help others by bringing my experience to policy.

By the time I made this decision, I had only three weeks before the application deadline, so I was hesitant to pour myself into the stress of writing applications for a totally new career path. I asked a few friends for advice, and they believed in me when I thought I didn’t stand a chance. Believing that the worst outcome would be to receive another rejection, I resolved to apply. At the time I was living in Germany, so I arrived to a cold, empty and gloomy Berlin to take the necessary graduate school exams during COVID. My first essay drafts were messy and lame to say the least. It took many hours, some filled with fear and panic, to get the applications in by the deadline. The other university I applied to rejected me right away, but I applied regardless. I pushed myself to have hope, to follow my principles, and not do what was comfortable, certain, or easy, but what was meaningful and necessary. In the end, that is a bigger statement about my character than whatever decision MIT would make about my application.

—————————————————

The news

I want to tell you about the moment when I received that admittance email and the reaction that followed: a mixture of joy, euphoria, and a bit of sadness. After living in four different countries overseas during the past 3 years, I was ready to settle down in Germany and find a community of friends and colleagues because the pandemic — or the Panini as I jokingly call it in an attempt to make the whole thing more lighthearted — has shown me how hard life can be when you face it alone.

The simple email was unexpected. It was late in the evening, and the email had been sitting three hours in my inbox before I realized it had arrived. My heart raced, and I ran towards my roommate in the kitchen, who jumped from seeing me so excited at such a late hour. I hugged him and I said emotionally, “I made it, they let me in.” I started to cry on his shoulder, as the warm mixture of emotions washed over me: the joy of having another chance to make a difference in the world and the sadness of leaving and having to start over again.

Once I washed my face and got myself together, and I forwarded the email to Ana, a mentor who helped me get started in nanotechnology research when I worked in Portugal. She answered my email, a mere fifteen minutes later, saying “Parabéns do fundo do coração! You truly deserve this,” and although I could see how my hard work and perseverance had paid off in the form of this admission, I didn’t see myself worthy of being at MIT.

The next day, I carefully examined every detail of that email to confirm that it was not a mistake. I felt a bit silly, but I figured that after 18 hours they should know if any mistake had occurred. I took a deep breath and I gathered up the courage to reply to the email and accept the offer of admission.

—————————-

Preparing to come

I made it to MIT, so that meant it was time to celebrate, right? Even though I wanted to celebrate, I could not bring myself to tell people about my acceptance. I told the friends who had checked on me during the application process and helped me calm down when I was anxiously waiting for the news. However, I avoided telling everyone on social media, as I felt it would bring too much attention to me, and then I would have to show up with a smile; when, in reality, the news created a lot of conflict inside me.

I was afraid of coming to the US. Experiencing the 2016 election while studying in Virginia showed me the strong racial divide, inequality, and stigma surrounding people from low-income backgrounds like myself. I saw first-hand how access to college education is a privilege in the US, and that scared me. Knowing that more than 60% of students at MIT come from the top 20% wealthiest families made me question if I could belong to the community of an elite university. I knew that professionally I could get by, learn the culture, and adjust. Studying in Europe taught me that I had the skills to adapt; however, adapting to their culture left me feeling unseen. I felt as if I had to hide how much I struggled to overcome poverty and support my family while excelling in academia.

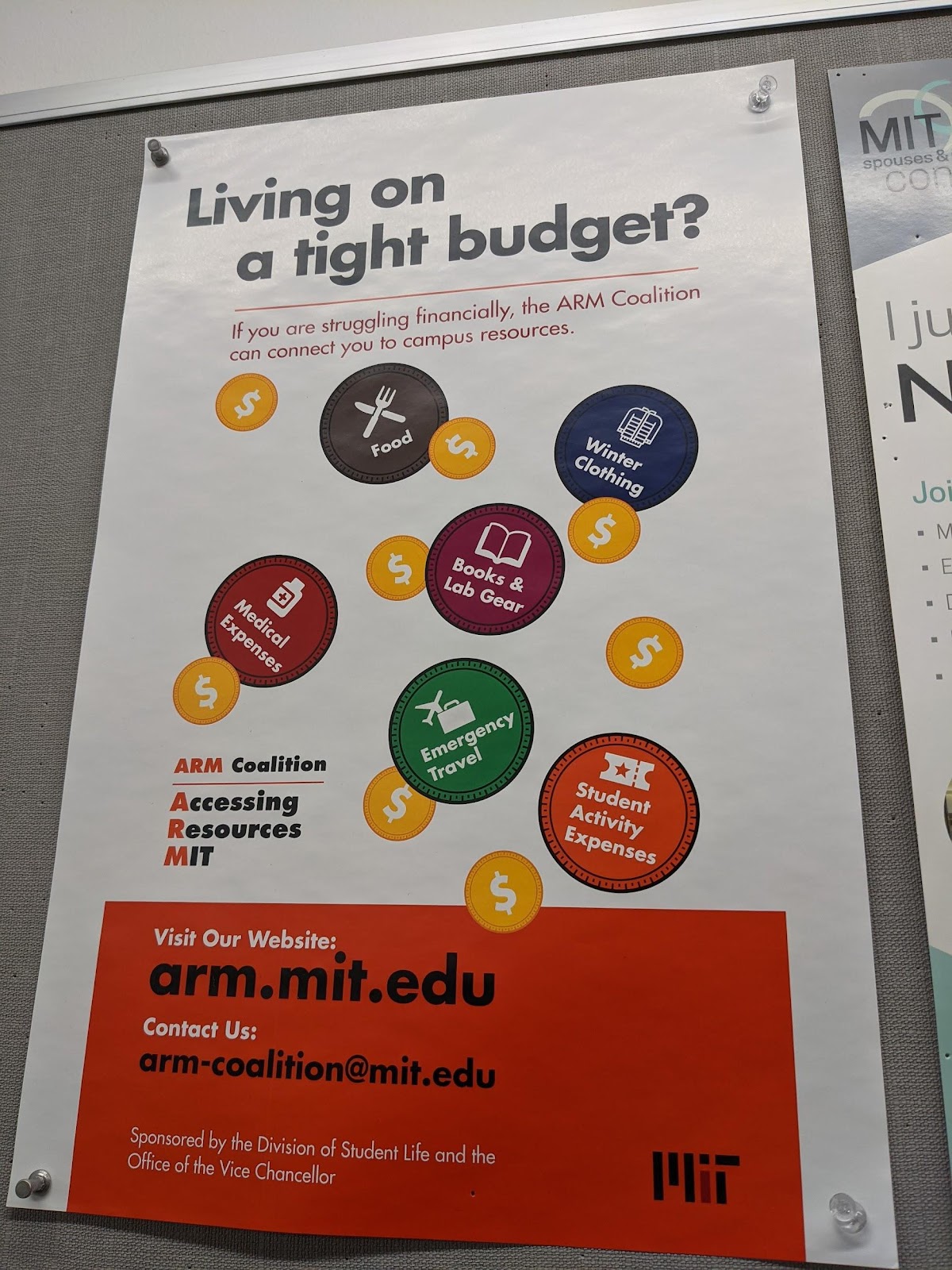

When I first walked into my department at MIT, this poster helped me understand that I wouldn’t need to hide anymore. 🙂

Slowly I began to tell people about my MIT acceptance, but I asked them to be discreet, as I didn’t want to become “the MIT boy”. I wanted people to remember who I was before that email, and I didn’t want people to change how they saw me because of MIT. I didn’t want to feel pressure to live up to their expectations. I didn’t want others comparing their achievements to mine as a metric to see if they deserved to come here. I didn’t want MIT to take over my life, my sense of self, and most importantly, my past.

In my experiences studying abroad prior to MIT, I had not met anyone from a similar marginalized background. Yes, growing up in rural Central America is hard, and facing the inequalities that exist in our society and education systems is scary and exhausting, especially as a first-generation college graduate. However, I didn’t go through those challenges to be admitted to MIT. I pursued college for other reasons, because I care about the world, and I care about people. I would have continued to pursue these goals regardless of if I had been accepted to MIT or not.

———————–

A statement of hope

Now, I want to walk everywhere around Cambridge, and I want to get to know all the parks in Boston. I want to make this place my new home. As I go with my colleagues to take photos at Killian Court in front of the famous MIT dome, I realize that I can belong here. I have met people who have struggled equally or even more than me to come here. I realized impostor syndrome is very pervasive, and although we chuckle about it, we are also empathetic and support each other through hard times. I don’t need to justify or defend my place in this university, or pretend I am qualified to be here. We all have different journeys, and people accept that, and that has been so important and so healing for me. Although this is not a perfect university, there are efforts to recognize mistakes and try to be better, and that gives me hope. I hope I can be compassionate with myself as I navigate this new identity as an MIT student. Fortunately, I am surrounded by generous, kind-hearted, and welcoming people, and these wonderful human beings have made dealing with the challenges and privilege easier than I expected.

Share this post: