With her new book, illustrator Felice C. Frankel hopes to make scientists and engineers better visual communicators.

Leda Zimmerman | Department of Chemical Engineering

It’s hard to look away from one of Felice Frankel’s images. For decades, Frankel, a research scientist in the MIT Department of Chemical engineering, has produced dazzling and witty art to tease and intrigue readers of the world’s most prestigious science journals. There is, for instance, the cover of PNAS featuring an illustration of paper wads floating casually atop a limpid surface, compelling even casual browsers to locate the article, “Lubrication with crumpled graphene balls.” And how about the distressingly long spoon full of sugars representing “Glycemic correction without immunosuppression” in Nature Medicine?

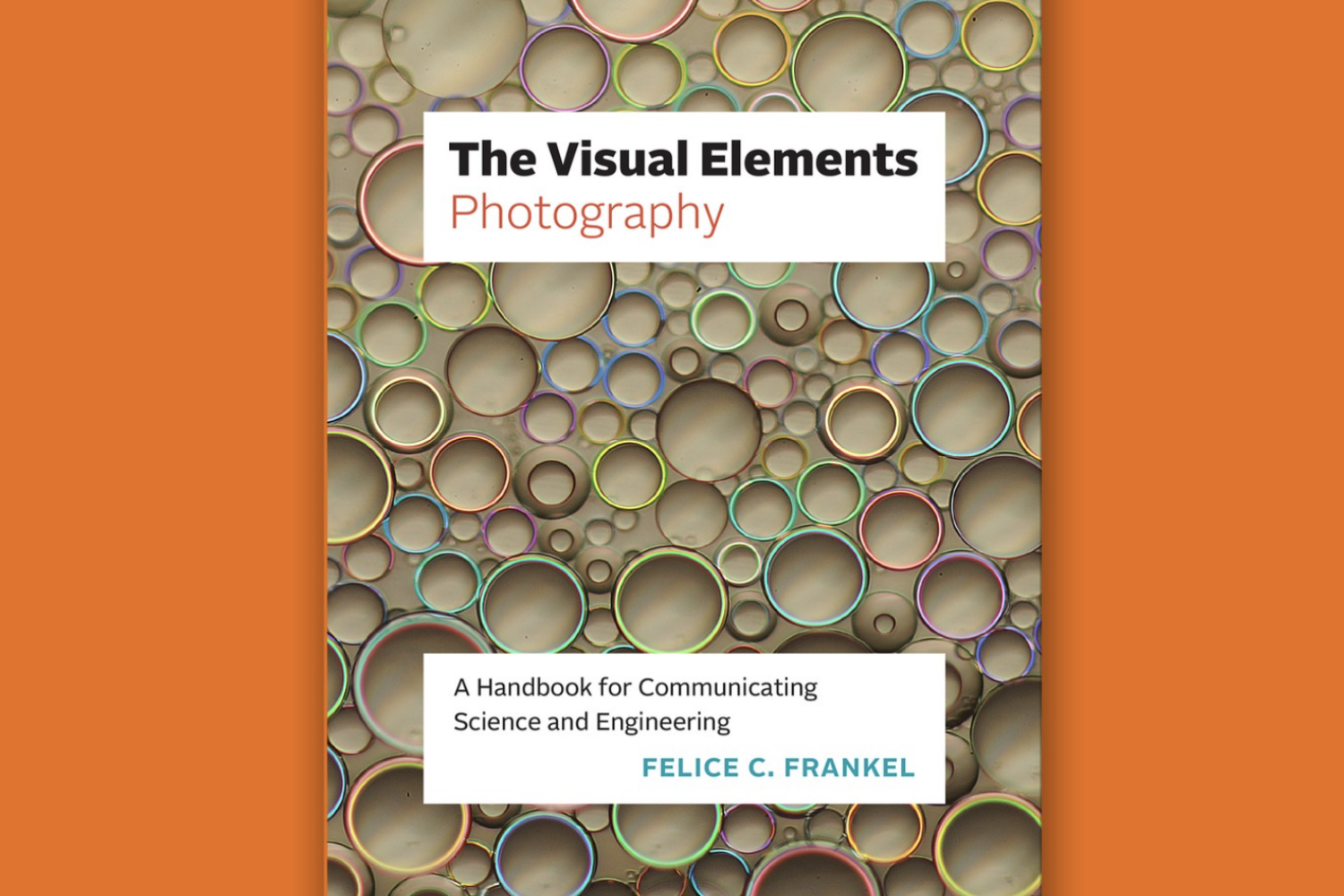

But while she may be best known for her published art — work that has been displayed in museums around the world — Frankel has spent decades as a teacher, training young researchers and established faculty to be effective visual storytellers. As part of that enterprise, she has just published “The Visual Elements: Photography” (University of Chicago Press, 2023), the first in a series of handbooks that collect and curate her methods of communicating research through images.

“I want to get information out to the larger world of engineering and science and medicine, so people working in those fields understand they can do what I’m doing,” she says.

This compact, 225-page primer highlights four devices Frankel has learned to exploit, in often ingenious ways: the scanner, phone, camera, and microscope. Her chapters break down the strengths and limitations of each of these tools, drawing on her experiences creating images with scientific collaborators.

“I sit down with researchers and push them to create a metaphor to describe what they are doing, which is how we come up with the idea for a picture,” says Frankel. “I want them to understand — especially the next generation coming up — that the process of communicating the essential pieces of your research is not just about making pretty pictures, but about advancing your own thinking, clarifying your own work in a way that’s accessible to non-experts.”

Sparking visual adventure

In her handbook, Frankel is equally painstaking about making her core concepts accessible to readers. Her many examples of image-making are delivered conversationally. “Even though they are not in front of me, I’d like to think my readers are engaged with me in a give-and-take,” she says. Her tone is often lighthearted and droll. In her chapter on the scanner, whose use in generating high-resolution images she pioneered, Frankel confesses, “I recently became obsessed with making images of eggs.” It turns out scanners can do wonders with raw whites and yolks.

There are stunning and unexpected views of agate, slime molds, electrolyzer technologies, microfluidic devices, a statue at the Isabella Gardner Museum, and a bubbling Bolognese pasta sauce — all presented in the process of imparting methods for optimizing backgrounds, cropping photos, selecting the right lighting, and determining the best resolution.

Frankel’s goal is to spark a spirit of visual adventure in her readers, an appetite for discovery that mirrors the process in a lab. “You can do this!” Frankel exhorts again and again. The book’s case studies, which include devising photographs for such prominent researchers as Moungi Bawendi, the Lester Wolfe Professor at MIT and a 2023 Nobel laureate in chemistry, are studded with anecdotes about experiments that don’t meet Frankel’s standards for scientific clarity and arresting composition. Play around, and find what works; “It can be fun,” she says. “I would go crazy with boredom if I used an identical setup for all my shoots.”

As much as she would like scientists and engineers to engage in visual experimentation, she knows how busy they are. “They may not have time to do this, but they can at least develop a visual literacy,” she says. “When they are composing images and graphics, I want them to be able to look at a picture and see how it could be better.” She also intends to make sure that researchers think hard about image integrity and communicating truthfully, as digital means for visual manipulation proliferate.

Frankel would be happy if her handbooks help plant the seed for a new generation of science photojournalists and she has been steadily chugging away on the series. Her second volume, “Design,” available in March, focuses on creating figures for journal submissions, poster designs, and slide presentations. It includes case studies by professional designers and illustrators. Frankel is currently working on “Abstraction,” which deals with finding great metaphors, modeling, diagrams, and notation. A fourth book will get its arms around data.

There’s great joy in this line of work, and Frankel wants to share it with others. “This series is a distillation of really 30 years of what I’ve been doing and continue doing,” she says. “The dirty little secret is that I’m learning the science as I’m making all these images. It’s a great, great job.”