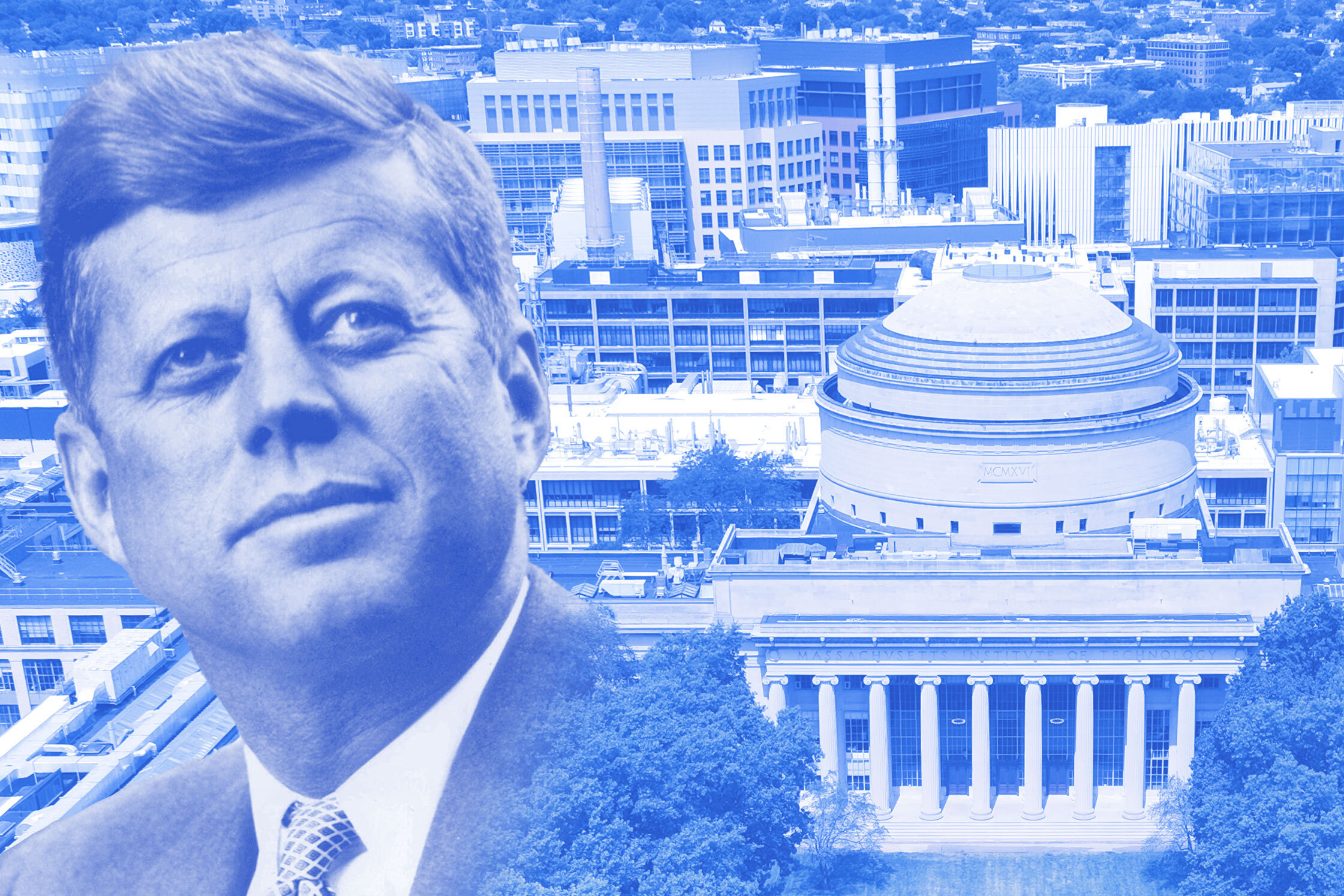

In the 60 years since President Kennedy’s death, a scholarship in his name has sent generations of British students to study tuition-free at MIT and Harvard University.

Lisa Capone | Office of the Vice Provost for International Activities

About 20 miles west of London, the meadow of Runnymede hosts a memorial to John F. Kennedy, dedicated by Queen Elizabeth II two years after the U.S. president’s assassination on Nov. 22, 1963. Situated on land bequeathed in perpetuity to the American people, the memorial overlooks the riverbank where the Magna Carta — a pivotal document prefiguring modern constitutional democracies — was sealed 800 years before. It’s an apt place for visitors to reflect on President Kennedy’s legacy of democratic leadership and service.

Across the Atlantic, the MIT campus hosts another British memorial to President Kennedy: the Kennedy Scholarship program. Conceived as a “living memorial” to complement the Runnymede monument and overseen by the Kennedy Memorial Trust, a U.K. charity, the Kennedy Scholarship program has kept the ideals of Kennedy’s presidency alive by sending generations of British students to Massachusetts to study tuition-free at MIT and Harvard University. Since the first cohort of Kennedy Scholars arrived in Cambridge in 1966, more than 570 U.K. citizens have traveled to the U.S. for graduate degrees, PhDs, and fellowships — often with life-changing consequences.

“It really did change the course of my whole life. It made possible some things I couldn’t have imagined,” says Richard Lester PhD ’80, a 1974 Kennedy Scholar who earned a doctorate in nuclear engineering at MIT after learning about the scholarship from a professor at London’s Imperial College. “That was for me a truly transformative moment.”

Lester, who hadn’t heard of MIT before that, stayed in the U.S. after his scholarship years and became a faculty member at MIT. He eventually served on the board of the Kennedy Memorial Trust and is currently the Institute’s vice provost for international activities and the Japan Steel Industry Professor in Nuclear Science and Engineering.

Like Lester, hundreds of British students got their first taste of America through the Kennedy Scholarship. Each fall, U.K. citizens who’ve earned British undergraduate degrees can apply for the scholarship, which covers tuition, fees, health insurance and living expenses, as well as stipends for U.S. travel following the academic year. Governed by a board of trustees, including appointees of the U.K. prime minister and the presidents of MIT and Harvard, the Kennedy Trust selects scholarship recipients in January, contingent on their acceptance into MIT or Harvard.

While Lester said the scholarship enabled him to pursue an academic field at MIT that wasn’t available elsewhere — the study of technologies and policies for nuclear safety and security, “the scholarship isn’t just about enabling a graduate education.”

“It is also about creating opportunities for the scholars to learn about the country,” he says. “Fifty years later, I am still learning about the U.S. and the scholarship puts people on that path.”

It’s a path that has produced an impressive group of alumni with a wide range of degrees, who are making a positive difference in the world as a result, said Kennedy Trust Director Emily Charnock. Charnock said trust founders chose MIT and Harvard in honor of President Kennedy’s interest in “bringing the sciences and humanities into conversation.”

“I think the values the Kennedy Scholarship program advances are still incredibly relevant in today’s more internationalized world.” Charnock says.

President Kennedy’s daughter, current U.S. Ambassador to Australia Caroline Kennedy, agrees, saying, “It is a great tribute to my father that the Kennedy Scholars come to the United States to learn, strengthen the U.S.-U.K. relationship, and help build a more peaceful and just world. I hope that spending time in the U.S. is as transformational for the scholars as my father’s time in England was in shaping his life.”

At its essence, Charnock added, the scholarship pays tribute to three core values associated with JFK: intellectual endeavor, leadership, and public service.

“Those qualities, in some combination, are really exemplified by Kennedy Scholars,” she says, adding, “We see public service in a broad way. It doesn’t have to be that traditional sense of government service or going into politics but contributing in some way to your community and the wider world.”

Exemplary of a scholarship recipient who still contributes in that way is David Miliband SM ’90, a 1988 Kennedy Scholar who studied political science at MIT, went on to become a Labour MP and Foreign Secretary in Britain and now serves as CEO of the International Rescue Committee. Other Kennedy Scholars have served in various high level government roles in both countries, as well as heading up impactful non-governmental organizations.

“It’s not a political scholarship, but the animating ideas about public service, internationalism, about commitment to others as well as yourself — you are forced to engage with that,” Miliband says. “There is a ripple effect that is not to be underestimated.”

Anil Jain PhD ’14, a 2009 Kennedy Scholar, is among those who credit the scholarship with steering their careers toward public service. Now principal economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington, Jain was pursuing a master’s in economics at the University of Cambridge when he learned about the scholarship through a poster. His decision to apply was “a major turning point” that routed him toward economic policy, rather than finance or another business-oriented field.

“Going into economics and the policy world has made me feel that I have an enriched professional life. Whenever there has been a big world event…I’ve always been glad that I’m working in government. There’s this idea of being able to do something, just being a small cog in trying to do something better,” Jain says. “The Kennedy Scholarship allowed me to do this PhD, this PhD allowed me to go into this policy role and in this policy role I am supporting the U.S. economy.”

Others who attended MIT through the Kennedy Scholarship either stayed at or returned to the campus in professional capacities.

“Winning a Kennedy Scholarship literally changed the direction of my career and life,” says Gareth McKinley PhD ’91, now the School of Engineering Professor of Teaching Innovation in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering and MIT’s representative on the Kennedy Scholarship Board of Trustees.

While studying chemical engineering at MIT in 1986, McKinley met his future wife, then a nursing student at Boston College.

“We got married in 1991 and decided to stay in the U.S. I applied to faculty positions and was lucky to get a job in the Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Harvard,” he said. “After teaching at Harvard for six years, I moved back to MIT in 1997 and I have been here for the last 26 years.”

Also teaching at MIT is former Kennedy Scholar Anna Stansbury, who attended Harvard on the scholarship in 2013 and is now assistant professor of work and organization studies at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Initially attracted to the scholarship by an interest in working in government, Stansbury said her scholarship year helped her realize the potential to influence public policy through an academic career.

“In that sense, the Kennedy Scholarship completely changed the direction of my life. The course of my professional life would have been nothing like it is now,” says Stansbury.

While the late president’s legacy is the stuff of history lessons for people of Stansbury’s generation, early scholarship recipients have memories of JFK — and his assassination.

“It was so determinative, that terrible moment in 1963,” says Emma Rothschild, who came to MIT in 1967 to study economics as part of the second cohort of Kennedy Scholars.

Chair of the Kennedy Memorial Trust from 2000 to 2009, Rothschild is now the Jeremy and Jane Knowles Professor of History at Harvard, where she also directs the Joint Center for History and Economics

“Students of my generation were thrilled at the possibility of going to the U.S., of being associated with President Kennedy’s name. Both MIT and Harvard were fascinating places,” Rothschild says. “1967 to 1968 was also a dramatic time in America and world politics. I was so excited to be at MIT.”

Later, as chair of the trust, Rothschild experienced that “sense of awe” again as she met and interviewed scholarship applicants — a group whose diversity has expanded over time, she says.

“They are such amazing young people who are interested in being Kennedy Scholars,” Rothschild says. “That really hasn’t changed.”

Crediting former MIT president (and Kennedy presidential adviser) Jerome Wiesner with helping shape the scholarship’s emphasis on connecting the humanities and sciences, Rothschild says the program’s success in fostering interdisciplinary conversations is its “great strength.”

Lester, a member of the eighth cohort of scholars, pointed out that, “the Kennedy presidency was an early memory for me and has remained part of my life.” In the decades since, Lester says, the U.K.’s living memorial has “brought JFK to life for generations of scholars.”

“Even though JFK has passed into history,” he says, “this program is as current today as it was in 1966.”