The MITES grant writer’s new book details her experience with epilepsy and offers lessons for creating a welcoming environment for workers with all kinds of health conditions.

Zach Winn | MIT News

Do you have a disability? It’s a question every employer is required to ask job applicants. Some people quickly check a box and move on. For Laura Beretsky, deciding how to answer the question is more complicated. Beretsky, who works as a grant writer in the MIT Introduction to Technology, Engineering, and Science (MITES) program, was diagnosed with epilepsy when she was 6. Prior to joining MIT, she had a major seizure at work. The experience was traumatic, but what bothered Beretsky even more was the way her co-workers and employer treated her afterward.

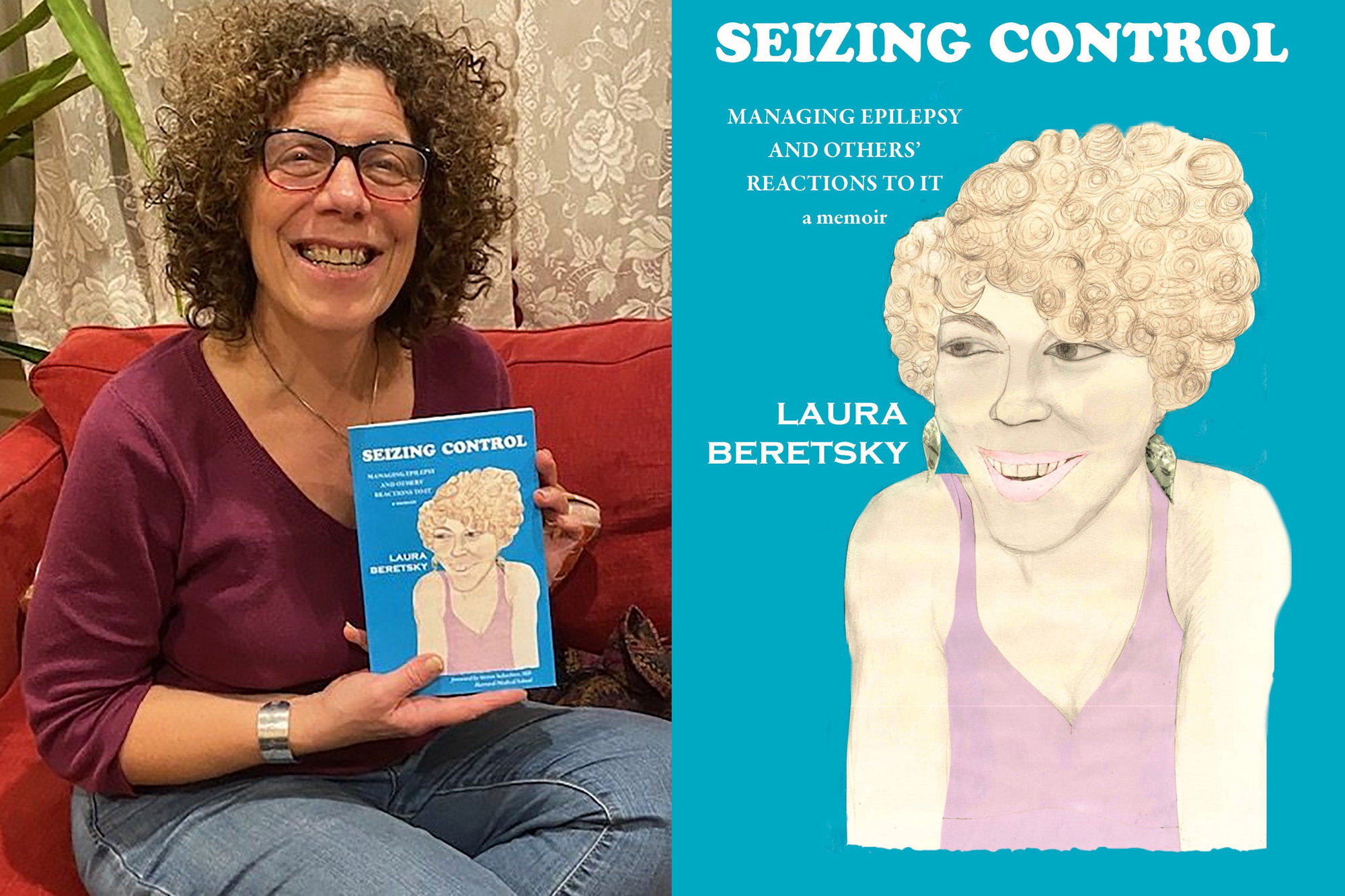

Beretsky recently released her memoir, “Seizing Control,” which details her journey with epilepsy, discrimination, and a major surgical procedure to reduce her seizures. After two surgical interventions, she has been seizure-free for eight years, though she notes she will always live with epilepsy. Now that her condition is “invisible,” she thinks long and hard about what box to check when employers ask if she has a disability.

Beretsky spoke with MIT News about her book as well as her disability advocacy work, and offered some lessons she’s learned throughout her journey.

Q: Why write this book?

A: Epilepsy is a bear to live with and widely misunderstood. There are a lot of stigmas attached to it. I wanted to put the word out there, partly to educate the general public, but also because everyone’s epilepsy is different, and everyone’s journey is going to be different, but I’ve learned a lot along the way that could be useful for people with epilepsy or anyone going through a major medical procedure.

I offer some universal lessons learned for anybody going through any major surgery or other medical procedure, which is most of us in the end — I’m giving my aging parents a lot of advice these days. What I realized is getting through that requires active participation on the patient’s part. Play a participatory, strong role in your own care. As patients, we really do know the most. We don’t have the intellectual, book knowledge that doctors have, but patients know the most about what’s going on in their bodies. My recovery was glitchy and I had to speak up, and I think that’s an important piece of getting the best care possible.

Also, part of my journey before coming to MIT involved workplace discrimination. I used the Americans with Disabilities Act as a tool to push back. It’s not okay to put out the vibe, “We don’t want you here because you had a big seizure in the office and that’s scary.” Seizures scare people, and so the book partly aims to explain what a seizure is and what it isn’t. They are scary to witness. That’s why I had this surgery. I had two young kids, and I knew it was scary for them. But people should be able to look beyond the condition itself when judging a person.

Q: What do you hope readers take away?

A: As a culture and a society, we need more courage and empathy, and that applies to many things, not just a seizure disorder. There are lots of people with conditions that present, that aren’t hidden, and we all have our biases about them, especially when they’re neurological, or brain-based. People with anxiety have panic attacks, for instance, and those symptoms can lead one to judge.

It’s about cultivating a sense of empathy and courage to be able to see someone going through something — whether a panic attack, seizure, fainting attack — and when you’re past the moment, the next time you see the person in the cafeteria, the office, any public space, being able to look beyond their condition and see them holistically as a person. I always say to people, “I want to be thought of as Laura the grant writer with the curly hair, not Laura the person with epilepsy that had a seizure at work.”

Q: What would your message be to employers trying to create a more inclusive workplace?

A: Having employee resource groups is a good first step. I also think training managers on what different health conditions look like is a good idea. We’ve held neurodiversity workshops at MIT, for instance. Employers can also host webinars and discussions around visible health conditions and neurodiversity, and make it clear that people should feel comfortable opening up about that. It’s a personal choice.

Some people might not want to discuss their health conditions, and many health conditions aren’t perceptible, but creating an atmosphere that makes people comfortable to discuss these things is an important piece of the solution. There are studies showing people with health conditions are happy in their workplace when they feel comfortable enough to speak openly about the condition.