How to hang in there

For one grad student, holding onto their scientific dreams involves more literal grip strength than you might think!

I was skimming the schedule of a conference last week when I saw the last thing any 6th year PhD student wants to see: a title that could describe my project, on someone else’s abstract. I froze with dread. Did I just get scooped?

No: the other project used a different experimental approach in a different model organism. Not a threat. When I saw this I was relieved, but still seriously rattled.

I’m studying the relationship between splicing and gene expression, a field that seems to get more popular every year. When I proposed an experiment as a second year in the summer of 2017 – bright-eyed, bushy-tailed and fired up on delusions of grandeur from success in undergrad – I thought it might take me a year or two to complete. After five years of singular devotion to this task, however, my lab notebook is bursting with chronicles of technical difficulties and conspicuously not bursting with publishable results. When my parents ask how much longer I’m going to be in school, I can’t tell them, because I literally don’t know! And to make things more fun, any day now someone else, with better luck or a wiser approach, might solve this problem first. As I returned to staring at another week’s worth of confusing data, months behind the schedule I envisioned last year, I felt a powerful urge to scream.

Eventually I put my experiments on ice and biked to the climbing gym.

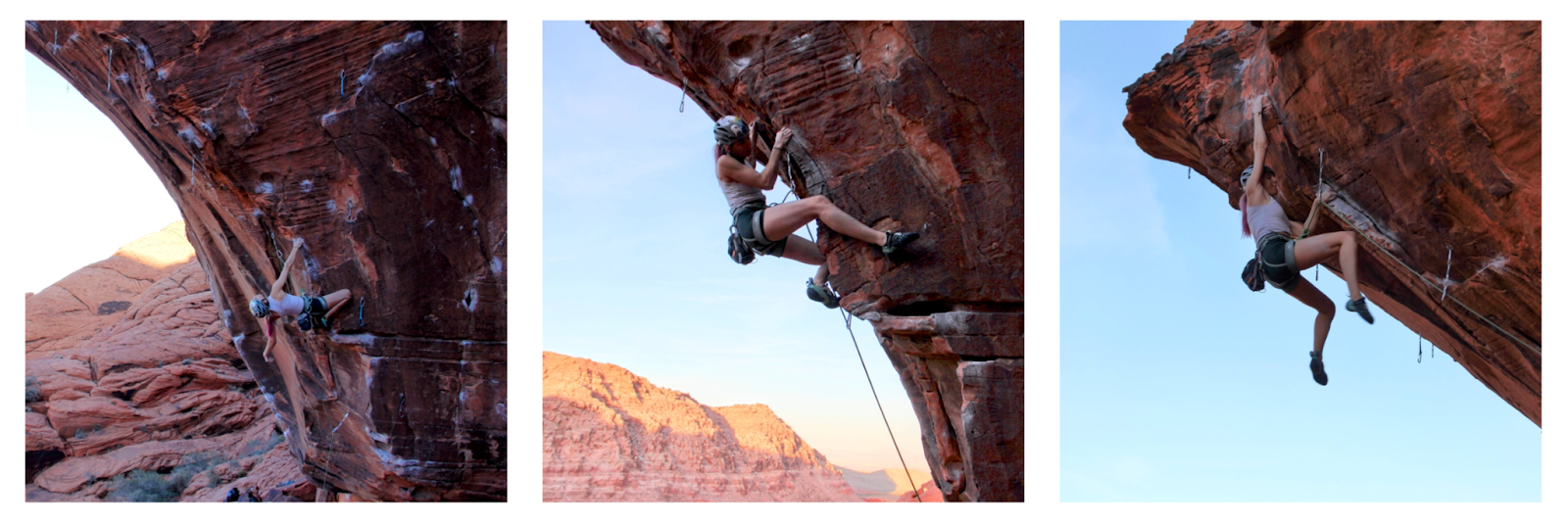

Me climbing at Alternative Crag in Red Rock Canyon, Nevada. Photos by Clayton Koob (@claytonkoob on Instagram)

There is a deeply comforting ritual to starting a climb. You cram your feet into tiny shoes. Thread a figure eight through your harness. Coat your hands in chalk, brush off the excess. Check your partner’s belay, check your knot. Deep breath. Then you pull on. And if the moment is right, you sink into a quiet river of flow. The scream fighting to escape your chest melts away. The tension and fear and panic melt away. Move by move you rise above the anxious buzz of the day, until you clip the anchors with only your own exhilarated breath in your ears.

Climbing well demands not only a broad repertoire of physical skills, but also the analytical ability to apply them to exquisitely variable challenges. A “moving meditation,” in the words of Lynn Hill, it utterly consumes your body and mind. Since starting in 2018 I have found a stunning richness and depth in climbing to explore, in its practice as well as its culture, history and community. My love of climbing has taken me on wild adventures, opened doors to phenomenal friendships, transformed my relationship to my body, and above all, sustained me through the long and lonely grind of PhD research.

It turns out nothing can really prepare you for how hard it is to “run your own show” – the goal of graduate school, according to a first-year advisor. You bear the full weight of responsibility for your project, for its success or failure, because this is your time to prove your worth as a scientist. You make hundreds of decisions every day about what to try next, when to persevere or change tactics, and you face the consequences of all of them. No one knows for sure what will work, but you are the one who may be set back weeks or months by a mistake. Of course if you are unfailingly deliberate, meticulous, and lucky, you might discover something new about life itself – not to mention reap all the associated benefits, such as the adulation of your peers and mentors, a high-impact publication, etc. That risk-reward exchange was thrilling to me five years ago. Lately, it feels unbearable.

I do wonder occasionally if it isn’t just me. Am I, emotionally, simply not cut out for this fickle, frustrating work? I can’t rule it out, but a perspective that I prefer is one another advisor gave me: that the only real determinant of success in the PhD is grit. Science is hard! Years deep in a project with an uncertain outcome, of course you’re not going to feel good. Perhaps the entire trick is to not give up, to persevere until an answer reveals itself. I like this lens, because looking through it I still have a shot. I am still coming into the lab every day, even when it feels terrible. Things are moving, albeit slowly. Maybe this doggedness is no more and no less than what success really looks like. And if it is, I think it’s fair to say the best thing I ever did for my science was to become obsessed with climbing.

Science attracts obsessive types. Indeed, a coveted ideal of academia is to derive enough fulfillment from your experiments that you don’t need anything else. I thought for a while that that could be me, but it is not. Research is a cruel lover. She can charm you into giving her the best years of your life, all the fight in your heart and your brain mustered on late nights and weekends alone at the bench, and leave you empty handed, or with a tangled mess of data that doesn’t contain the answer you were seeking. Eventually I realized I needed to balance my work with another obsession outside of the lab, to source some joy elsewhere, or I would lose the will to keep coming back.

Though climbing is in many ways parallel to science, the important attributes for me are the ways in which they are orthogonal to one another. For example, the quantitative, incremental, surefire nature of progress in practice of a physical skill such as climbing is incredibly different from the ambiguity and frustration of experimental research. Time and effort put in translate reliably, linearly, into results. It restores one’s faith in an orderly universe. A day spent climbing outdoors, moreover, is the precise antidote to a day spent hunched at the bench, manipulating microliters and wondering if it will ever matter to anyone. Being outside in nature, expansive and breathtaking, reminds me why I fell in love with biology in the first place. Using my whole body, making big movements with big muscles, taking big falls, I reboot my tired mind with the powerful cleansing agents of adrenaline and dopamine. When I’m building an anchor I feel vividly present with the knowledge that my actions matter in the simplest and oldest way anything can matter: for my immediate survival.

After a few hours at the gym, I biked back to the lab and finished the experiments I had set up earlier. I was tired but happy, humming to myself and luxuriating in little reminders of my session – soreness in my shoulders, the smell of chalk on my clothes. I jotted down notes for the next day’s experiments, even getting excited about a new approach. I have no idea where science will take me, or how long it will take to get there, but I do know one thing: without climbing I simply could not do it.

Me climbing at Orange Crush in Rumney, New Hampshire. Photo by Anthony Wong.

Share this post: