An ode to Kenji’s Cooking Show

How home cooking during the pandemic helped me gain a new mentor

At the start of the pandemic, my cooking skills were in top form. I had mastered scrambled eggs and had honed my selection criteria for one pot pastas (the simpler, the better). However, the pandemic and the subsequent shutdown revealed some gaping holes in my knowledge.

I was suddenly home all the time, afraid of eating out, and forced to eat my own cooking for three meals every day. Eating under-seasoned, overcooked pasta mush rapidly became unsustainable.

At the same time, I was falling into a lot of YouTube rabbit holes, one of which was populated by home chefs. I watched hours of these knife-wielding YouTubers puttering around their home kitchens, preparing meals of varying complexity and all promising high degrees of deliciousness. Out of all of them, I came back to one time and time again: J. Kenji Lopez-Alt, an MIT alum, author of The Food Lab, and a household name among my peers whose home cooking I aspired to.

I highly recommend checking out any of his videos, but for now, picture this: the video opens to a middle-aged dad speaking to a GoPro: “Hey everyone, it’s Kenji, and today we’re making…” The view flips momentarily to the floor while he straps the camera to his forehead and starts moving around his kitchen. He shows us all of his prep work and the majority of the cooking time (everything except long bake times in the oven or simmers on the stovetop). His MIT training comes out in his careful explanations of his actions, for example: why many restaurant chefs prefer to cook without gloves (it encourages them to wash their hands more often), what an emulsion is (imagine your oil and vinegar salad dressing being held together with a finger trap), the best way to cut different types of alliums (spoiler alert, there is a mathematical model involved for onions); the list goes on. And at the end of it all, he takes his plate out to the natural light of his backyard to give us a glamor shot while he samples his food (“Mmm!”) and shares a scrap of it with his rescue dog, Shabu.

Maybe part of the reason I took so readily to Kenji’s Cooking Show is that I am a wet lab biologist who had recently been deprived of the full lab experience, and Kenji managed to address all of my experimental needs in his videos. Each dish was an experiment; Kenji’s discussions of kitchen chemistry using sponges and finger traps provided the theory. His head-mounted camera provided a helpful point of view that facilitated my learning of the techniques, with the added benefit that I could slow down and rewind the video when needed, as in his demonstration of cutting scallions. When “I can do that,” and “I want to try that,” became recurring thoughts, I finally rolled up my sleeves and got my hands dirty at the bench, a.k.a. my kitchen counter.

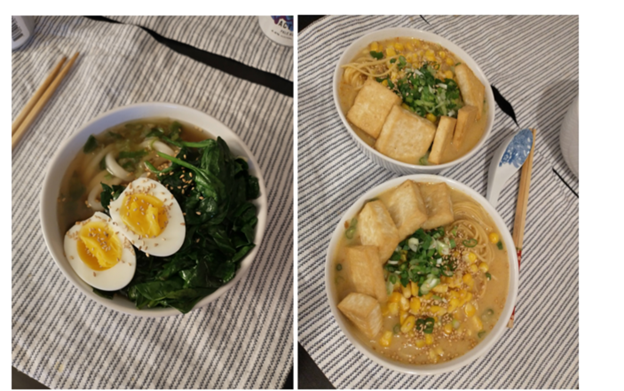

As with any experiment, sometimes things failed in different and exciting ways: things got overcooked, my dishes were under-seasoned, or I mis-timed the various components. I learned to troubleshoot on the go, to taste intermediate steps and adjust for seasoning. I gathered a new set of equipment and reagents specific to these experiments: knives, spices, various auxiliary kitchen tools. I finally figured out what doneness of pasta worked both for immediate eating and to prevent my leftovers from completely falling apart. I made dishes that weren’t pasta-based! I learned what a pinch of salt meant: somewhere south of Kenji’s liberal fistfuls but still enough to elevate the flavors of the dish.

Aside from the technical aspects, Kenji’s Cooking Show also managed to meet my need for mentorship in this time when lively discussions about fresh data in the lab were in short supply. Between the real-time, largely unedited style and the first person point of view, Kenji’s videos felt vastly more accessible to me compared to other cooking YouTubers. His inclusion of his mistakes, sassy written commentary, and explanations of flexible techniques inspired confidence that not all is lost if I made a tiny mistake, and significantly diminished my fear of trying. For example, I practiced making carbonara, a notoriously finicky recipe, to the point where it became one of my weeknight go-to dishes. Over the course of many attempts at his recipes and others, I gained the confidence to try new things, to fail, to learn, and to try again.

My kitchen skills grew under the tutelage of my new cooking mentor, and I know now that there’s so much more to learn and to try. And interestingly enough, now that things are slowly starting to reopen in the wake of the pandemic, I find that I eat out less because I can rely on my home cooking to produce nutritious, delicious, and joyful meals that fuel experimentation at home and in the lab.

Share this post: