Science at Sea

My week aboard the R/V Roger Revelle

This October, I embarked on the adventure of a lifetime. I was enrolled in Elements of Modern Oceanography, a course taught by scientists in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program, and my professor was the chief scientist on an upcoming research cruise. She mentioned that there were a few extra spots and I jumped at the opportunity.

We set sail on the R/V Roger Revelle for a week-long journey. We departed from Woods Hole, a quaint town in Massachusetts renowned for marine research, into the Atlantic. Our mission was to collect data and retrieve previously deployed instruments while riding the Gulf Stream around the Atlantis II Seamounts.

Roger Revelle is one of the 5 global-class research ships in the United States, meaning it can operate anywhere on the planet. Navigating the powerful currents of the Gulf Stream would be a breeze for this ship. Stepping aboard felt surreal. I could hardly believe I had the chance to be on such an iconic vessel. The interior, though compact, was thoughtfully designed. The layout was a bit confusing at first—deck “1” was the main deck, with lower decks numbered incrementally. My bunk was on deck 2, which was below the main deck and essentially underwater, while decks 02, 03, and 04 rose above the main deck. Rooms were assigned based on seniority, so more experienced scientists and technicians scored the rooms on higher levels with the coveted windows.

I was excited, though slightly nervous about what to expect. Thankfully, my worries were unfounded. My cabin was cozier than I had anticipated, despite my broken thermostat. The temperature hovered comfortably around 60°F. The rooms resembled compact dorms, complete with bunk beds but with a nautical twist: anti-skid surfaces on dressing tables and drawers and cabinets designed to stay closed unless specifically opened—preventing them from banging with the ship’s movement. The bunks even had curtains for privacy, ideal for the rotating day and night shifts that scientists and crew members followed. Those curtains ensured that even if my roommate was on a different schedule, our sleep wouldn’t be interrupted.

We spent a day and a half in transit, during which we had time to relax and bond. I spent much of it on the deck, mesmerized by the endless ocean. There was no one else around as far as the eye could see and the solitude was oddly comforting. At sunset, I was thrilled to see groups of dolphins racing toward the ship and playfully riding the bow waves.

Internet access was limited and staring at a laptop screen made me seasick. However, the ship had plenty of facilities to keep us engaged. It was equipped with a library, board games, a cardio room, and even a ping-pong table. I gave the treadmill a try—running while the ship rocked was a unique balancing act. Ping-pong, surprisingly, was less affected by the ship’s movement than I expected. Being in such close quarters with a small group of people encouraged friendships as we shared meals, games, and stories to pass the time.

As night fell, we reached our research site, and the real excitement began. I was on a night shift from midnight to noon and my first task was to assist with coring. With help from our marine technicians, Jenny and Jeremiah, we set all the relevant equipment up on deck. Under the stars, we lowered a 2,000-ton gravity core down to the ocean floor to collect deep-sea mud. We were over the abyssal plains, which are vast open stretches of deep ocean floor where organic matter settles, forming a nutrient-rich ooze that marine geologists are eager to study. After deploying the core off the ship deck, we had to wait two hours for it to reach the seafloor, which was five kilometers deep. We monitored for a drop in tension on the line to confirm the core had reached the bottom. Then we began the slow process of bringing it back up.

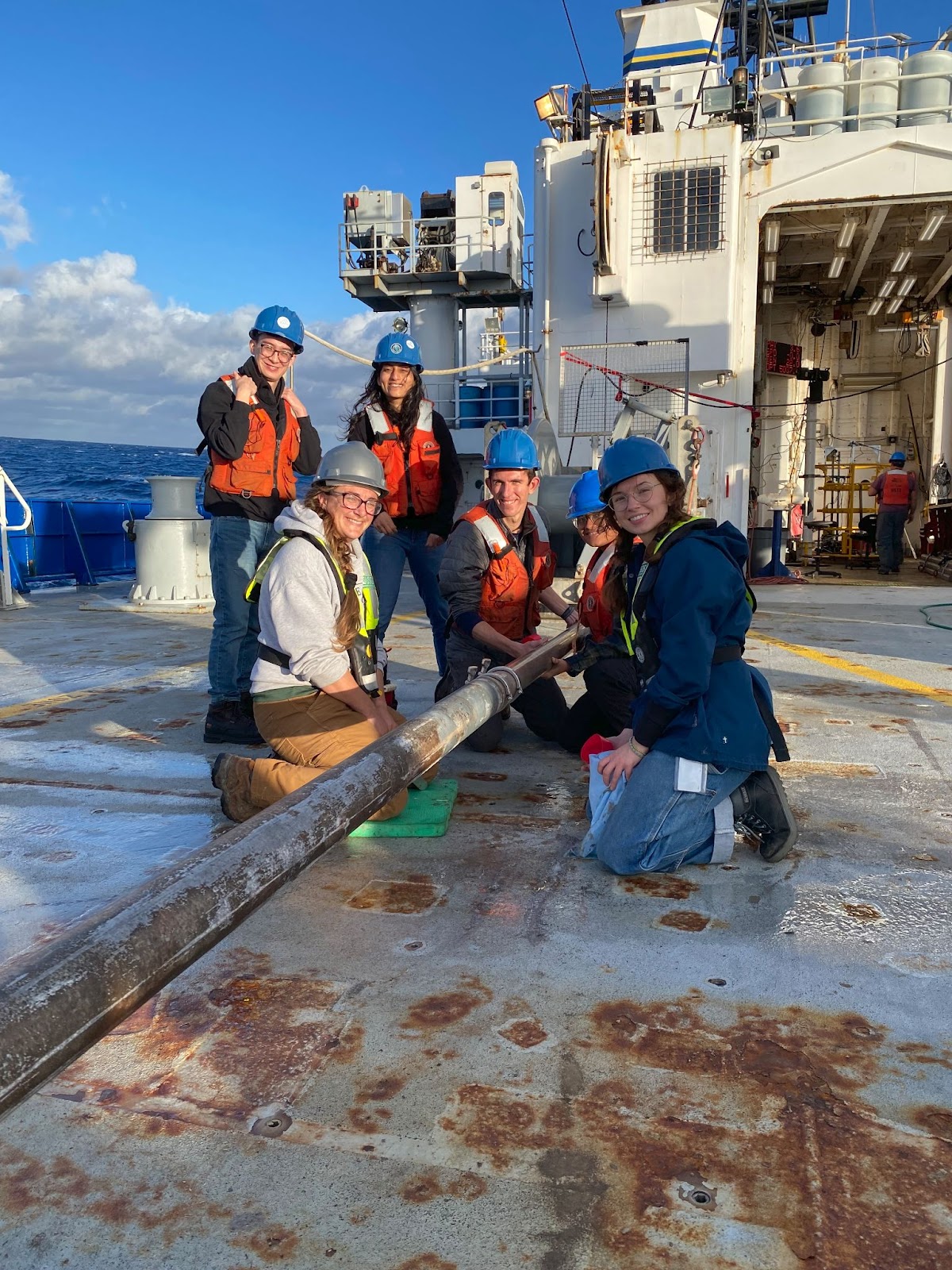

During the wait, a few of us went up to the main deck to stargaze. The sky was partially clear, and we were treated to a glittering canopy of stars, gently swaying with the motion of the ship. After another two hours, we finally retrieved the core. The mud was wet and silty to touch. I was overcome with a profound sense of awe as I realized that this seemingly ordinary mud had been a part of the deep ocean, preserved for centuries or even millennia. We carefully prepared the sample for storage.

Next, we deployed a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature, Depth sensor), a workhorse of oceanographic research. The CTD collects data on the water’s salinity, temperature, and pressure at various depths, which helps scientists understand the vertical structure of the ocean. Since many factors in oceanography vary more with depth than across horizontal distances, CTD casts provide valuable insights into the water column.

At noon, after having a delicious lunch for dinner, I collapsed into my bunk. The rocking of the ship and the pitch-black darkness of my windowless room made for some of the best sleep I’d had in a while.

I fell in love with the ocean in those early dawn hours, just before sunrise. Its beauty, dynamism and power made it feel almost alive. The different textures of the water were mesmerizing—some I had never seen before. There were blue pointy peaks that looked like a goth disco and patches that looked like leather. At times, the waves were so strong they sent water spraying upward and when the sunlight hit it just right, it formed little rainbows.

As the week drew to a close, I realized this wasn’t just a thrilling adventure—it was a reaffirmation of why I chose this path. There’s something humbling about studying the ocean’s depths, knowing that every sample and every data point contributes to our understanding of this vast, mysterious ecosystem. My professional goal of working in marine conservation might seem unconventional, but opportunities like these at MIT are helping me make it a reality. The cruise may have ended, but my journey into marine science has only just begun.

Preparing the deep-sea core sample for storage

R/V Roger Revelle docked at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

Share this post: