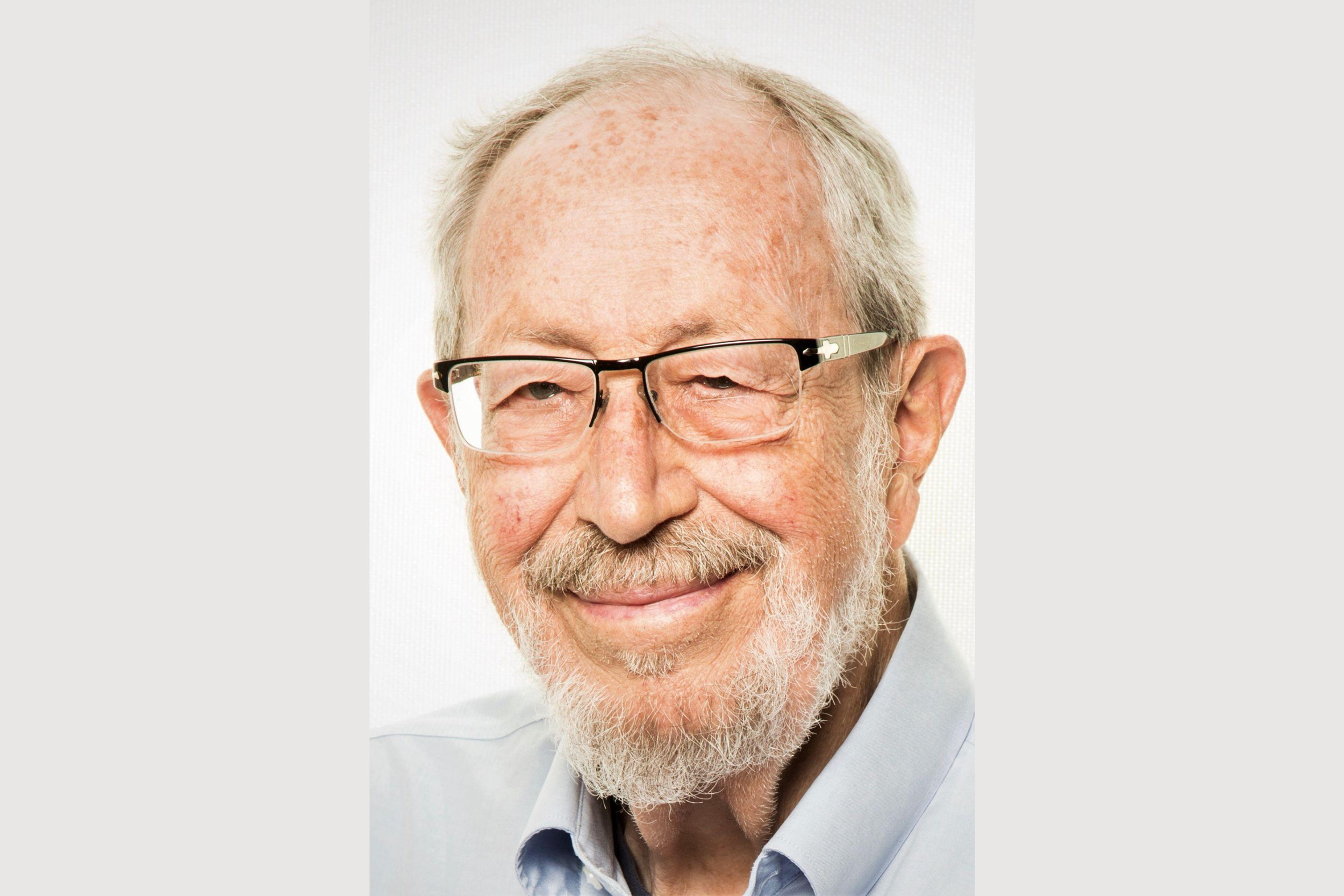

A faculty member at MIT Sloan for more than 65 years, Schein was known for his groundbreaking holistic approach to organization change.

Meredith Somers | MIT Sloan School of Management

Edgar H. Schein, a social psychologist who bridged the academic and pragmatic sides of culture and organization by practicing his own tenets on humble leadership and inquiry, died Jan. 26. He was 94.

Schein, who was the Society of Sloan Fellows professor of management emeritus at MIT Sloan, joined the school in 1956, when it was still known as the MIT School of Industrial Management. During his 67-year tenure, Schein authored dozens of books on social science subjects including career dynamics, organization culture, group dynamics, and interpersonal interactions. His three-tiered model of organization culture and writings on relationships and trust are still used by managers today.

“Most people are either one or the other: They’re big thinkers and they have these grand theories, or they do research and incremental work to understand phenomena better,” says Douglas (Tim) Hall PhD ’66, a professor emeritus of management and organizations at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business. “Ed could do both. I can’t think of anyone else who had the kind of range that he had.”

Schein was born in Zurich, on March 5, 1928. He came to America in 1938 and in the early 1950s entered the U.S. Army’s clinical psychology program. After he earned his PhD in social psychology from Harvard University in 1952, he served in the army until 1956. During his service, Schein interviewed American prisoners of war about indoctrination attempts conducted by Chinese captors fighting on behalf of North Korea during the Korean War.

In a 2012 interview with Indiana University’s Tobias Leadership Center, Schein said talking with ex-POWs brought him to the concept of coercive persuasion.

“I discovered in that setting and then in other settings that if I have you physically captive, I can influence you if I choose to. It applies to the POWs, but it applies equally to the golden handcuffs,” Schein said. “If I’m economically committed to [an] institution, I have tenure, I am going to allow myself — or be forced — to be socialized into their culture. There is no gain in being a dissident or a deviant if I’m stuck there. If I’m stuck there, I’m going to sooner or later be influenced.”

Another of Schein’s enduring ideas involved people’s values and their career choices: What motivates someone to work? What central values drive one’s career? How do employees want to be managed or rewarded? The answers to these questions determine a person’s career anchors.

Career anchors, Schein wrote in a 1974 report, are a “motivational/attitudinal/value syndrome which guides and constrains the person’s career.”

Schein initially identified five career anchors but later added three more. The eight anchors are general managerial competence, technical/functional competence, entrepreneurial creativity, autonomy/independence, security/stability, service/dedication to a cause, pure challenge, and lifestyle.

“On the one hand, [a career] is anchored in a set of job descriptions and organizational norms about the rights and duties of a given title in an organization,” Schein wrote. “On the other hand, the career is anchored in a set of needs and motives which the occupant is attempting to fulfill through the work he does and the rewards he obtains for that work — money, prestige, organizational membership, challenging work, freedom, etc.”

Schein collaborated on the subject of careers with MIT Sloan’s John Van Maanen, professor of organization studies emeritus, and MIT Sloan professor emerita Lotte Bailyn. The work inspired the formation of a careers division in the Academy of Management.

For Jennifer Chatman, a professor of management at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, Schein’s work in defining organization culture was groundbreaking. Schein “brought a level of discipline and precision” to a concept that did not lend itself to focused study, says Chatman, a co-founder and co-director of the Berkeley Culture Center. The center hosts an annual conference that includes an Edgar Schein Best Student Paper Award.

Originally published in 1985, Schein’s book “Organizational Culture and Leadership” proposed that organization culture can be analyzed on three levels. He outlined these levels in Sloan Management Review:

- Artifacts. The constructed environment of an organization, including its architecture, technology, office layout, dress code, visible or audible behavior patterns, and public documents like employee orientation handbooks.

- Values. The reasons and/or rationalizations for why members behave the way they do in an organization.

- Assumptions. Typically an unconscious pattern that determines how group members perceive, think, and feel.

MIT Sloan senior lecturer Donald Sull, who teaches on work culture and toxic environments, says Schein’s work revealed “the deeply held assumptions and values that lie below the waterline but profoundly shape behavior on a day-to-day basis.”

MIT Sloan’s Van Maanen remembered Schein as someone who was vibrant but also kind and decent, with a quiet demeanor; he wasn’t pushy.

“He was an imaginative listener who could really break through a conversation with the right question at the right time,” Van Maanen says. “That was Ed’s modus operandi: to listen very carefully.”

That concept of careful listening is a foundational piece of Schein’s writings on helping and humble inquiry.

According to Schein, self-effacing inquiry is the art of drawing someone out by asking questions to which you do not already know the answer, thereby building a relationship based on curiosity and interest in the other person.

It’s the highest-ranking leaders who most need to learn this skill, he believed.

“Our culture emphasizes that leaders must be wiser, set direction, and articulate values, all of which predisposes them to tell rather than ask,” Schein wrote in his book “Humble Inquiry.” “Yet it is leaders who will need humble inquiry most, because complex interdependent tasks will require building positive, trusting relationships with subordinates to facilitate good upward communication.”

Schein developed a method for consciously shifting culture within an organization, and within that method he identified tools that leaders have available to them to effect change, including:

- What a leader regularly focuses on, measures, rewards, and controls.

- How leaders distribute resources and rewards.

- Criteria used for recruitment and retention, performance management, and dismissal.

Schein understood that organization change went below surface level, UC Berkeley’s Chatman said. Organizations want their employees to be working toward collective objectives, but if leaders aren’t seeing desired outcomes, they can’t just issue an edict and expect everything to change.

“In that sense, he had a holistic view of organizations that you can’t just change the incentive system, or you can’t just have the leader tell people to do something different,” Chatman said. “You have to look at all of these touch points so that you can drive holistic change that makes sense to people.”

In recent years, Schein also devoted much of his time to advocacy around global warming, eventually co-organizing a collection of invited essays titled “Social Scientists Confronting Global Crises.”

Schein is survived by his daughters Louisa Schein (Ernie Renda), Liz Krengel (Wally), and his son and business partner Peter Schein (Jamie). He also leaves seven grandchildren — Alex, Peter and Oliver Krengel; Sophia and Ernesto Renda; and Annie and Stephanie Schein — as well as great-grandsons Logan, Caius, and William Edgar.