A summer class teaches PhD students and early-career archaeologists ceramic petrography, revealing the origins and production methods of past societies.

Jason Sparapani | Department of Materials Science and Engineering

Jennifer Meanwell carefully placed a pottery sherd — or broken fragment of ceramic — under the circular, diamond-coated blade of a benchtop saw.

“Cutting the sample is the first big step,” says Meanwell, a lecturer in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at MIT. She was leading a lab in making thin sections of pottery for petrographic analysis, a method used to examine ceramics and determine their composition, structure, and origins.

“You want a slice that’s thin enough to work with but thick enough to maintain its structure through the rest of the process.”

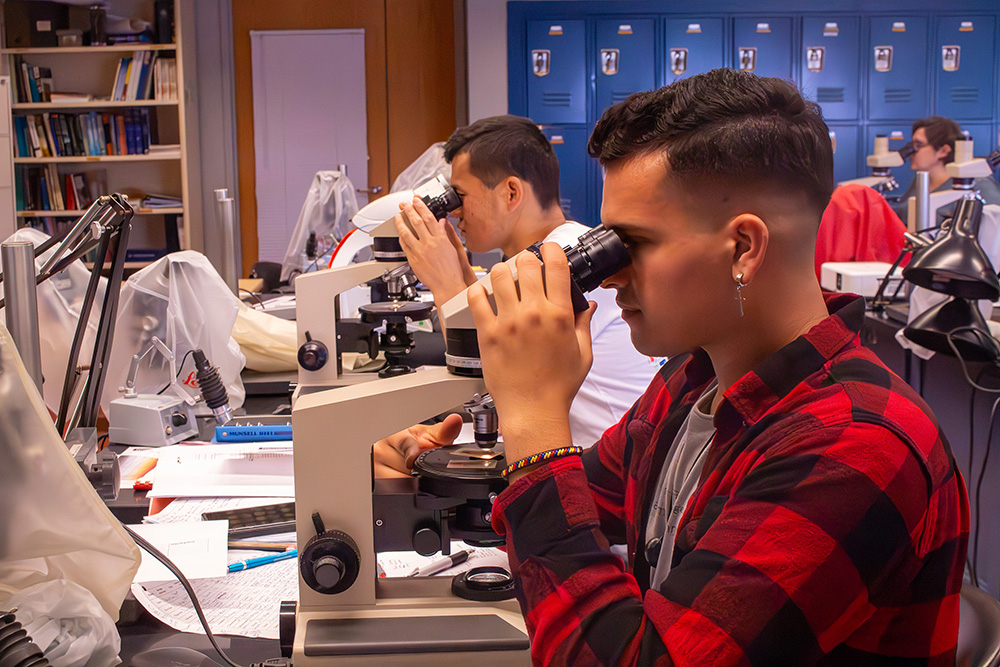

The lab was part of a summer intensive course at MIT for PhD students and early-career researchers in ceramic petrography, a specialized skill in archaeology. The course focuses on using optical microscopy to characterize pottery from ancient civilizations, revealing information about manufacturing techniques and provenance.

Twelve students from North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia participated in the three-week course in June to develop advanced skills, enriching students’ understanding of ancient ceramics and their broader historical and cultural contexts. It included morning seminars in mineralogy and archaeological theory and hands-on laboratories to identify and characterize materials, understand how they were manufactured, and infer what they were most likely used for.

Meanwell and Senior Technical Instructor William Gilstrap taught the group how to examine pottery samples collected from around the world — Greece, Mexico, and the Middle East — using polarized light microscopes to examine the materials.

“Polarized light will transmit through a mineral at 30 microns in a predictable manner — it interacts with its structure, and the optical properties help us identify which mineral types they are,” says Gilstrap. By determining the minerals, researchers can link them to the geological landscape they came from. “This helps us know more about how people interacted with their environments, and perhaps, how people transferred knowledge on time and space.”

Hands-on training

The course builds on the two-semester-long class Materials in Ancient Societies, run by the Center for Materials Research in Archaeology and Ethnology (CMRAE), a consortium of eight Boston-area schools that provides training in archaeological and ethnographic materials. Few institutions globally teach ceramic petrography, and most provide short, one- to two-week courses.

Gilstrap highlighted the need for extended training. “It takes time to develop the skills to find the nuances in the structure as well as to learn mineralogy, geology, and the manufacturing techniques of ceramics,” Gilstrap says.

Students learn to reconstruct the production methods of past ceramics, from cooking pots to roof tiles, by examining the underlying structure of materials to determine how they were made. For example, they can identify whether a vessel was crafted by pinching, a technique in which a potter presses into a ball of clay to form indentations, or coiling, which involves stacking rope-like strands of clay to build up the vessel’s walls. This analysis can reveal production, transport, and consumption patterns.

“We can see where things are made. We can see where things ended up and direction of exchange. And that’s the basics of an economy,” says Gilstrap.

The course blends sciences and humanities, covering basic chemistry, geology, and anthropological theory. Students also learn how to make their own petrographic thin sections — slices of pottery impregnated in epoxy and mounted on glass slides. These sections are essential for microscopic analysis of the ceramic’s composition and structure. Most researchers, however, typically do not make their own thin sections. Instead, they send their samples to specialized labs, where the preparation process costs approximately $45 per sample.

“When you have 300 samples, that gets costly,” Gilstrap adds.

Applying new skills

This practical experience resonated with Jean Paul Rojas and Michelle Young, from Vanderbilt University’s anthropology department. As did all the students, they brought in their own slides for analysis. Theirs were made by a colleague two decades ago.

“These have never been petrographically analyzed, so it would be the first time looking at them and trying to identify the petro groups,” says Rojas, a PhD student in archaeology. His research focuses on human migration, exchange, and movement in the Caribbean, particularly the mineralogical origins of ceramics.

Before the MIT summer course, Rojas had little training in geology or mineralogy. Two weeks in, he joked, “I know what rocks are now.”

“Now I feel like I know how to really look at all these different minerals, the feldspars and the quartz and the plagioclase — the different types of feldspars — the micas, and I can identify them and make something useful out of it.”

Young is an assistant professor in Vanderbilt’s anthropology department and Rojas’ thesis advisor. She’s always had an interest in materials science and ceramics, and she’s collaborated with a petrographer in the past.

“But in order to truly understand the data, I needed an introduction into the technique,” Young says.

When she returns to Vanderbilt, she plans on including petrography as one of the techniques featured in a lab sciences course for non-science majors.

“I am hoping at some point that I will eventually publish on petrographic results, or at least use the technique as a very preliminary way of grouping different ceramics,” Young says.

Another summer course student, Anna Pineda, a PhD candidate from the Philippines studying at the Australian National University, is analyzing jar burial sites in the islands and archipelagos between Southeast Asia and the Pacific Ocean. She’s particularly interested in understanding how mineral analysis techniques in geology can inform archaeology.

“When I talk to geologists, they can’t really get what I want to do unless they have an archeological background,” Pineda said. “It’s good to have a perspective from people who do archaeology.”

Pineda plans to incorporate knowledge gained from the course into her PhD research.

“Hopefully, I can get better results out of research on materials that have never been studied yet, using methods that aren’t commonly applied, in Island Southeast Asia.”