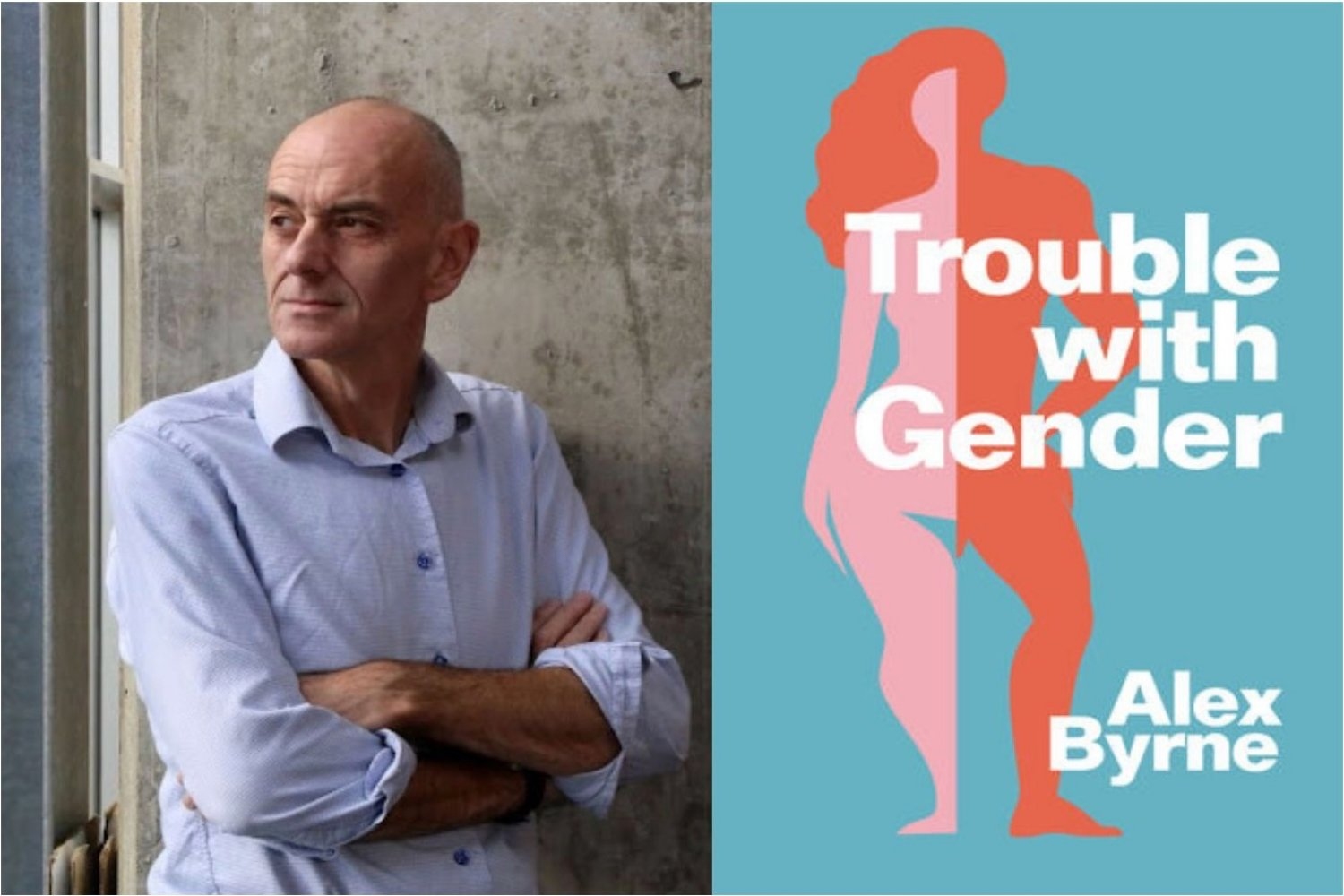

In “Trouble with Gender: Sex Facts, Gender Fictions,” MIT Professor Alex Byrne argues for a return to a more inclusive brand of philosophical inquiry.

Benjamin Daniel | School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

MIT philosopher Alex Byrne knows that within his field, he’s very much in the minority when it comes to his views on sex and gender.

“As an example, I have a particular answer to the question ‘What is a woman?’ Namely, that a woman is an adult female of our species. This is extremely controversial, believe it or not, in philosophy. In fact, almost all the experts in philosophy who’ve discussed this question think that my answer is wrong.”

In his new book, “Trouble with Gender: Sex Facts, Gender Fictions,” published by Polity, Byrne argues for reasoned and civil conversation on an issue he says has unfortunately become an outlier in his field.

“Philosophy is the one discipline where you’re allowed to raise any question or discuss anything without fear of reprisal,” Byrne says. “Philosophers have traditionally valued an attitude of toleration for outrageous or offensive views.”

A marketplace of challenging ideas

Antagonism to ideas usually arrives from outside philosophy, Byrne says. However, he says in the case of sex and gender, the philosophical environment can, at turns, appear actively hostile to and exclusionary of ideas that fall outside what he describes as “progressive orthodoxy.”

“Previous social justice campaigns — the civil rights movement, gay marriage, women’s right to vote — relied on verifiable claims for their success and to avoid legal challenges,” Byrne argues.

Challenges to arguments about minorities’ rights and giving women the franchise occurred in a hotbox of sociopolitical and ideological tumult. But, Byrne says, the arguments happened. Views were considered, discarded, reexamined, and incorporated into the corpus of shared information.

Not so with sex and gender, he believes.

“Some philosophers have been ostracized by their colleagues or have been driven out of the profession altogether,” Byrne says.

Byrne further argues that some ideas regarding sex and gender have not been properly examined by philosophers because of the aforementioned progressive tilt in philosophical circles.

For example, Byrne counts himself among those who support trans rights.

“But when you’re on the trans rights side, then there’s immense pressure to agree with a statement like ‘trans women are women,’” says Byrne. “Lots of philosophers in my view have succumbed to that pressure and agreed with it without having any argument for it.

“Avoiding dissent runs the risk of overlooking valid counterarguments,” Byrne adds. “Often the heretics don’t have a point — but sometimes they do.”

Social progress, Byrne says, is not aided by intellectual bubbles.

On reasoned discourse

Byrne is a leader of MIT’s Civil Discourse project, an initiative that invites experts from across academic disciplines to openly discuss controversial ideas. When asked how civil discourse about sex and gender might look in practice, he points to this strategy.

“Remove the guardrails and allow for open, spirited debate,” Byrne says. “Students are much more resilient and open-minded than we tend to think.”

Once you can answer an initial question, Byrne says, other questions arise. The exercise is meant to tease out the best ideas and give them room to breathe.

Byrne believes in a set of core principles for effective discussion and debate: avoiding “cosseting in advance” and ensuring arguments about sex and gender or other challenging topics take place in good faith.

“Discomfort and emotions are okay,” Byrne says. “Too much safety can make matters worse.”

Effective, civil discourse, Byrne argues, is inclusive and allows for everyone to shop in the marketplace of ideas.