When he isn’t investigating human motor control, the graduate student gives back by volunteering with programs that helped him grow as a researcher.

Michaela Jarvis | School of Engineering

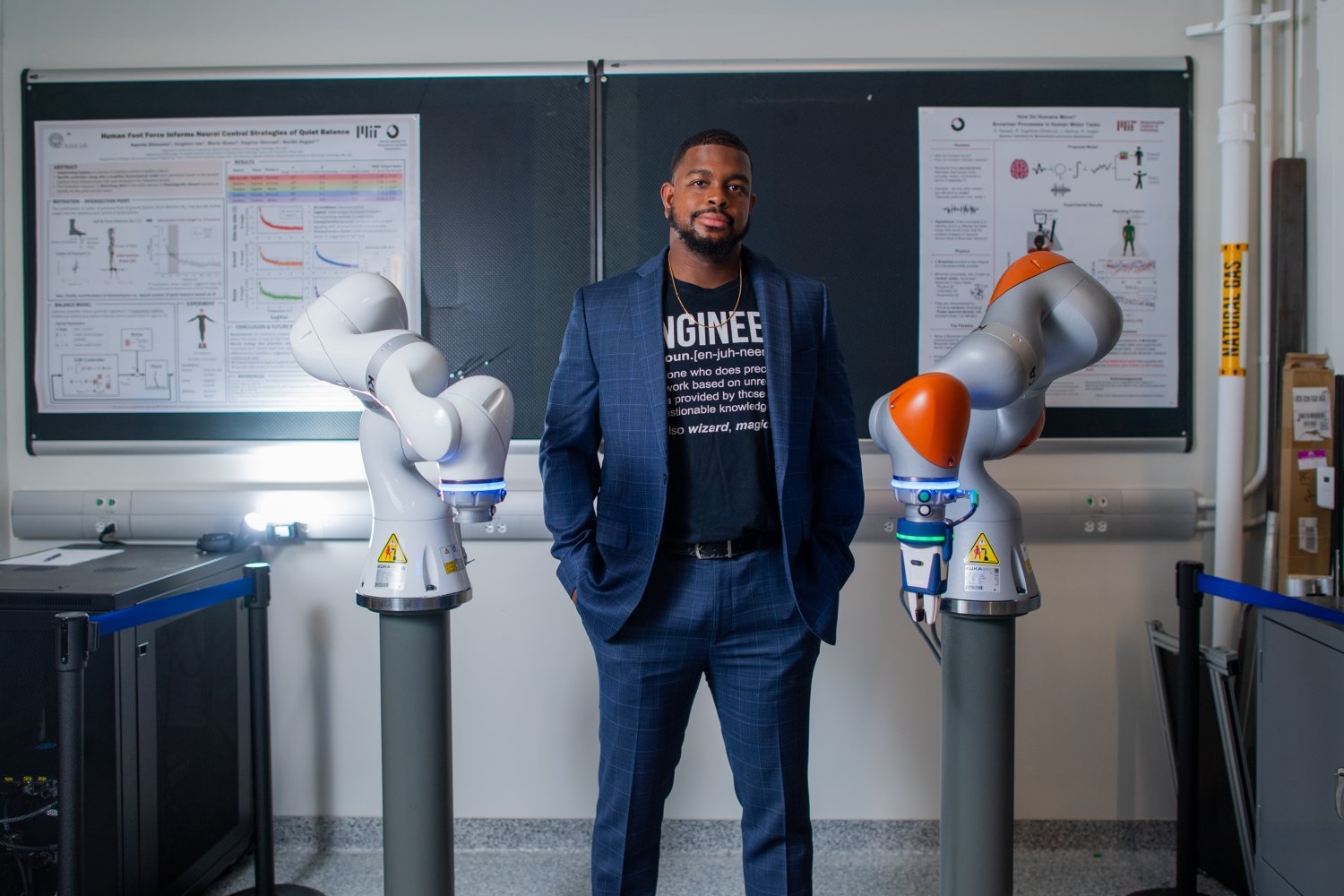

An accomplished MIT student researcher in health care robotics, with many scholarship and fellowship awards to his name, A. Michael West is nonchalant about how he chose his path.

“I kind of fell into it,” the mechanical engineering PhD candidate says, adding that growing up in suburban California, he was social, athletic — and good at math. “I had the classic choice: You can be a doctor, a lawyer, or an engineer.”

Having witnessed his mother’s grueling residency when she was training to be a doctor, and feeling like he didn’t enjoy reading and writing enough to be a lawyer, “That left engineer,” he says.

Luckily, he enjoyed physics in high school because, he says, “it gave meaning to the numbers we were learning in mathematics,” and later on, his major in mechanical engineering at Yale University agreed with him.

“I definitely stuck with it,” West says. “I liked what I was learning.”

As a rising senior at Yale, West was selected to participate in the MIT Summer Research Program (MSRP). The program identifies talented undergraduates to spend a summer on MIT’s campus, conducting research with the mentorship of MIT faculty, postdocs, and graduate students to prepare program participants for graduate study.

For West, MSRP was an education in what “exactly grad school was, especially what it would be like at MIT.”

It was also, and most importantly, a source of validation that West could succeed in the higher levels of academia.

“It gave me the confidence to apply to top grad schools, to know that I could actually contribute here and be successful,” West says. “It very much gave me the confidence to walk into a room and approach people who obviously know way more than I do about certain topics.”

With MSRP, West also found a community and made enduring friendships, he says. “It’s nice to be in spaces where you get to see a lot of minorities in science, which MSRP was,” he says.

Having benefited from the MSRP experience, West gave back once he enrolled at MIT by working as an MRSP group leader for two summers. “You can create this same experience for people after you,” he says.

His involvement as a leader and mentor in MSRP is just one way West has sought to give back. As an undergraduate, for example, he served as president of his school’s National Society of Black Engineers chapter, and at MIT, he has served as treasurer for the Black Graduate Student Association and the Academy of Courageous Minority Engineers.

“Maybe it’s just a familial thing,” West says, “but being a Black American, my parents raised me in a way that you always remember where you come from, you remember what your ancestors went through.”

West’s current research — with Neville Hogan, the Sun Jae Professor in Mechanical Engineering, in the Eric P. and Evelyn E. Newton Laboratory for Biomechanics and Human Rehabilitation — is also aimed at helping others, especially those who have suffered orthopedic or neurological injury.

“I’m trying to understand how humans control and manage their movement from a mathematical standpoint,” he says. “If you have a way of quantifying the movement, then you can measure it better and implement that to robotics, to make better devices to help in rehabilitation.”

In 2022, West was chosen to be an MIT-Takeda fellow. The MIT-Takeda Program, a collaboration between MIT’s School of Engineering and Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company, primarily promotes the application of artificial intelligence to benefit human health. As a Takeda Fellow, West has studied the ability of the human hand to manipulate objects and tools.

West says the Takeda Fellowship gave him time to focus on his research, the funding allowing him to forgo working as a teaching assistant. Although he loves teaching and hopes to secure a tenure-track position as a professor after earning his PhD, he says the time commitment associated with being a teaching assistant is significant. In the third year of his PhD, West devoted about 20 hours a week to a teaching position.

“Having a lot of time to do research is great,” he says. “Learning what you need to learn about and doing the research gets you to the next step.”

In fact, the type of research that West conducts is especially time-intensive. This is at least partly because human motor control involves much automatic, subconscious activity that is predictably difficult to understand.

“How do people control these complex, subconscious systems? Understanding that is a slow-going process. A lot of the findings build on each other. You have to have a solid understanding of what is known, what is a working hypothesis, what is testable, what is not testable, and how to bring the non-testable to testable,” West says, adding, “We won’t understand how humans control movement in my lifetime.”

To make progress, West says he has to carefully proceed one step at a time.

“What are the small questions I can ask? What are the questions that have already been asked, and how can we build upon those? That’s when the task becomes less daunting,” he says.

In September, West will begin a fellowship with the MIT and Accenture Convergence Initiative for Industry and Technology. Hoping to encourage and facilitate interaction between technology and industry, the corporation selects five MIT-Accenture fellows each year.

“What they’re looking for is someone whose research is translational, that can have impacts in industry,” West says. “It’s promising that they’re interested in the basic, fundamental research I’m doing. I haven’t worked on the translational side yet. It’s something I’d like to get into after graduation.”

While earning prestigious fellowships and advancing human-robot interactions in health care, West is still very much the laid-back guy who “fell into” engineering. He finds time to meet with friends on the weekends, took up rugby as a graduate student, and has a long-distance relationship with his fiancée, with a wedding date set for next summer.

Asked how he will counsel his future students when they approach complicated work, he has a predictably relaxed response.

“Don’t be afraid to ask for help. There’s always going to be someone who’s better at something than you are, and that’s a good thing. If there weren’t, life would be a little boring.”